Hornby Island Sea Lion Study - January 2005

For

the last five years I've been traveling to

Hornby Island, BC to dive

and play with the Stellar sea lions that migrate there during the winter

months to wait to feed on the annual herring spawn. They are an incredibly friendly

bunch who are accustomed to divers visiting and interacting with them.

This year we ran into one special pup who appeared to be "instrumented".

The dive lodge owners were aware of the animal, but not aware of any studies

under way in their area at the time. I sent some photos of him to Donna

Gibbs at the Vancouver Aquarium whom I had met on previous specimen

collecting trips in British Columbia and asked if she had heard of any

studies going on at Hornby. She had not but told me she'd ask around the

local marine biologists' community. A month later I received a response from

Peter Olesiuk from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Turns out the blue headed guy I ran into on Hornby was one of twelve

instrumented animals that are part of this year's study on foraging behavors.

Peter generously gave his time to explain the details of the study to me by

email. I have found the information on the behaviors and travel

patterns of these guys so interesting from Peter's study that it makes you

look at sea lions in the water in a whole new way, curious how long they've

been at their current site and how far they've traveled in the last few

months. Below is the full context of Peter Olesiuk's combined mail

thread on the study. More images from the trips can

be found here.

For

the last five years I've been traveling to

Hornby Island, BC to dive

and play with the Stellar sea lions that migrate there during the winter

months to wait to feed on the annual herring spawn. They are an incredibly friendly

bunch who are accustomed to divers visiting and interacting with them.

This year we ran into one special pup who appeared to be "instrumented".

The dive lodge owners were aware of the animal, but not aware of any studies

under way in their area at the time. I sent some photos of him to Donna

Gibbs at the Vancouver Aquarium whom I had met on previous specimen

collecting trips in British Columbia and asked if she had heard of any

studies going on at Hornby. She had not but told me she'd ask around the

local marine biologists' community. A month later I received a response from

Peter Olesiuk from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Turns out the blue headed guy I ran into on Hornby was one of twelve

instrumented animals that are part of this year's study on foraging behavors.

Peter generously gave his time to explain the details of the study to me by

email. I have found the information on the behaviors and travel

patterns of these guys so interesting from Peter's study that it makes you

look at sea lions in the water in a whole new way, curious how long they've

been at their current site and how far they've traveled in the last few

months. Below is the full context of Peter Olesiuk's combined mail

thread on the study. More images from the trips can

be found here.

Marty Steinberg.

I am a marine biologist specializing in marine mammals,

and along with my colleagues Steve Jeffries from Washington Fish and

Wildlife, and Andrew Trites from University of British Columbia, are

conducting a study on foraging behaviour of Steller sea lions. We deployed

instruments on 12 Steller sea lion in January at Norris Rocks off Hornby

Island this year. Our goal is to determine how foraging patterns vary

between sex- and age-classes, which will hopefully lead to a better

understanding of why populations in Alaska have been declining. A leading

hypothesis is that young animals are nutritionally stressed, especially if

high-quality energy-rich prey are unavailable. The instruments we deployed

include a back-mounted recorder that monitors feeding activity (indicated by

stomach temperature transmitted from a pill in the stomach) that will be

released after two weeks (we've already recovered that package from the

animal you photographed), another back-mounted time-depth recorder that is

monitoring haulout and diving patterns, which we will plan on releasing and

recovering in April, and a head-mounted satellite tag that is providing

information on movements. The instruments are colour-coded, and the animal

you photographed off Hornby is our smallest animal - a 222 lb fellow about a

year-and-a-half old that is still nursing. Compared to older animals, our

preliminary finding suggest these young dependent animals, and their

mothers, may be less mobile than other sex- and age-classes, and thus more

limited in their ability to take advantage of locally and seasonally

available prey resources. These young animals and their mothers seem to

hang around the same area for extended periods, where we've had other

animals move hundreds of kilometers (two have almost circumnavigated

Vancouver Island).

By the way,there is also a branded Steller sea

lion in the photos - 145Y. The animal was branded as a pup on Rogue Reef

off Oregon in July 2003 by my colleagues with ODF&W (Oregon Dept of Fish &

Wildlife). I'm keeping track of resightings for them and will pass this one

along. They are tracking the branded animals to determine survival and

reproductive rates, and we are also learning much about movements.

Interestingly, moms with young animals tend to disperse quite far from

rookeries where they breed, but then the youngsters tend to park on a

particular haulout site while mom is off foraging.

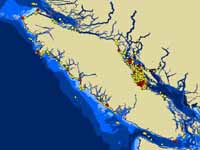

It

will be a while before our study is complete and all the information

processed. We tagged 12 sea lions this year, and hope to do 12-15 again

next year. The attached map shows the locations received by satellite

(yellow indicates at-sea locations, and red indicates on land, with larger

circles representing more accurate positions). As you can see, the main

foraging area has been in the northern Strait of Georgia, where herring

stocks have been staging in preparation for spawning. One of our goals is

to monitor sea lion movements as the herring spawn and disperse, and sea

lions switch to other prey. The complete story won't be told until we

recover the time-depth recorders in April, which will provide very detailed

information on diving and haulout behaviour (at 10 sec intervals over a

period of several months!). Although most of the animals have been foraging

in the northern Strait of Georgia, you'll notice a few positions out on the

west coast. These represent the longer-range movements of two subadult

males. One headed south out through Juan de Fuca and up the west coast of

the Island and is currently sitting at Hope Island off the north tip of

Vancouver Island. The other headed north through Johnstone Strait and then

down the west coast of Vancouver Island, and is currently sitting at Cape

Alava off the Washington coast. Interestingly, these animals seem to

know where all the traditional haulout areas are situated, and make frequent

stopovers at them.

It

will be a while before our study is complete and all the information

processed. We tagged 12 sea lions this year, and hope to do 12-15 again

next year. The attached map shows the locations received by satellite

(yellow indicates at-sea locations, and red indicates on land, with larger

circles representing more accurate positions). As you can see, the main

foraging area has been in the northern Strait of Georgia, where herring

stocks have been staging in preparation for spawning. One of our goals is

to monitor sea lion movements as the herring spawn and disperse, and sea

lions switch to other prey. The complete story won't be told until we

recover the time-depth recorders in April, which will provide very detailed

information on diving and haulout behaviour (at 10 sec intervals over a

period of several months!). Although most of the animals have been foraging

in the northern Strait of Georgia, you'll notice a few positions out on the

west coast. These represent the longer-range movements of two subadult

males. One headed south out through Juan de Fuca and up the west coast of

the Island and is currently sitting at Hope Island off the north tip of

Vancouver Island. The other headed north through Johnstone Strait and then

down the west coast of Vancouver Island, and is currently sitting at Cape

Alava off the Washington coast. Interestingly, these animals seem to

know where all the traditional haulout areas are situated, and make frequent

stopovers at them.

*******************************************

Peter F. Olesiuk

Marine Mammal Biologist

Head, Seal and Sea Lion Program

Conservation Biology Section

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

Pacific Biological Station

Nanaimo, B.C.

Photo courtesy of Peter Olesiuk

Photo courtesy of Peter Olesiuk

For

the last five years I've been traveling to

Hornby Island, BC to dive

and play with the Stellar sea lions that migrate there during the winter

months to wait to feed on the annual herring spawn. They are an incredibly friendly

bunch who are accustomed to divers visiting and interacting with them.

This year we ran into one special pup who appeared to be "instrumented".

The dive lodge owners were aware of the animal, but not aware of any studies

under way in their area at the time. I sent some photos of him to Donna

Gibbs at the Vancouver Aquarium whom I had met on previous specimen

collecting trips in British Columbia and asked if she had heard of any

studies going on at Hornby. She had not but told me she'd ask around the

local marine biologists' community. A month later I received a response from

Peter Olesiuk from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Turns out the blue headed guy I ran into on Hornby was one of twelve

instrumented animals that are part of this year's study on foraging behavors.

Peter generously gave his time to explain the details of the study to me by

email. I have found the information on the behaviors and travel

patterns of these guys so interesting from Peter's study that it makes you

look at sea lions in the water in a whole new way, curious how long they've

been at their current site and how far they've traveled in the last few

months. Below is the full context of Peter Olesiuk's combined mail

thread on the study. More images from the trips can

be found here.

For

the last five years I've been traveling to

Hornby Island, BC to dive

and play with the Stellar sea lions that migrate there during the winter

months to wait to feed on the annual herring spawn. They are an incredibly friendly

bunch who are accustomed to divers visiting and interacting with them.

This year we ran into one special pup who appeared to be "instrumented".

The dive lodge owners were aware of the animal, but not aware of any studies

under way in their area at the time. I sent some photos of him to Donna

Gibbs at the Vancouver Aquarium whom I had met on previous specimen

collecting trips in British Columbia and asked if she had heard of any

studies going on at Hornby. She had not but told me she'd ask around the

local marine biologists' community. A month later I received a response from

Peter Olesiuk from the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Turns out the blue headed guy I ran into on Hornby was one of twelve

instrumented animals that are part of this year's study on foraging behavors.

Peter generously gave his time to explain the details of the study to me by

email. I have found the information on the behaviors and travel

patterns of these guys so interesting from Peter's study that it makes you

look at sea lions in the water in a whole new way, curious how long they've

been at their current site and how far they've traveled in the last few

months. Below is the full context of Peter Olesiuk's combined mail

thread on the study. More images from the trips can

be found here.